Author: Srimanta Mitra

I have been an avid Murakami fan for two years now. I first started reading his novels when I was in my first year of college when one day in the library I found a book with a semi-naked woman on the cover of a book authored by a man whose name seemed really familiar (in fact it was a friend of mine who had mentioned to me very enthusiastically, earlier in the week, that this Japanese author Haruki Murakami is really great).

That book was Sputnik Sweetheart, the first I ever read by Haruki Murakami. This first book was an unforeseen and indecipherable experience, like an enigma (instead of a dish) served on a plate. Murakami was, at the time, an author whose works I wanted to read solely and only because he was a mystery to me: in isolation his words and sentences sometimes made sense, but as a cohesive whole his books always eluded me.

And now, after several years and a total of 14 books later, Murakami is no longer the mysterious author that he once was. It’s not as if I hold him in any less regard than I did so many books before, but what has happened is that his motives and his devices have become so easily comprehensible, so predictable in and of themselves, that Murakami has become his own cliché. Again, it’s not as if that’s a bad thing. You can reduce most authors to clichés, including some of my very favourites: In a book by Dostoevsky, you’ll have a lowly, suffering, emaciated person (typically a man) who falls in love with yet another lowly, suffering, emaciated person (typically also a prostitute or a similarly ‘fallen’ woman), with a lot of social commentary, delivered in a bitingly satirical manner, and an unhealthy obsession with one’s own thoughts. In fact, there’s a word in the Russian vocabulary—dostoevschina—that means precisely this. So it’s absolutely not a stretch to say that authors have had a profound influence on the cultures of which they were a part.

Murakami, similarly, can be pigeonholed into a categorical little box of his own: his books are set in a meta-universe somewhere at the edge of the world where reality has already ended and the life after reality has not begun, a kind of suspended metaphysical limbo in which all his characters reside and go about their daily business, without meaning and without caring to find it. He has several other tropes, involving cats, strange and fascinating dreams, fatalism, worms, and rock-hard penises with erections that don’t subside. Aside from his caustically dry sense of humour, which is also very hard to detect at times, it is important to note perhaps the most prevalent of all his tropes: loneliness.

All of Murakami’s characters are filled with a sense of loneliness that they can never get rid of: like a pathological condition, it continues to haunt them for as long as they are alive, and sometimes even after they are dead. They all do their work like dehumanized robots working at a mass-production factory, then they make some food (or order it from somewhere), have some sex, and go to sleep—only to repeat the same routine the very next day.

Murakami is often looked at as a magical realist, but in my opinion, he shares his ideas more closely with the French surrealists who took the stage in the second decade of the 20th century. The surrealists’ manifesto included the simple idea of abstracting oneself from everyday bourgeois reality, so that greater emphasis can be laid on the motives of the unconscious, so that not only do we live our lives, we also understand why we live them in a particular way. Murakami does much of the same, except in the 21st Century rendition of surrealism: his focus is no longer on understanding merely the unconscious, but the world that exists beyond man and nature, a world which we have been cut off from merely because we are alive.

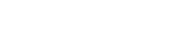

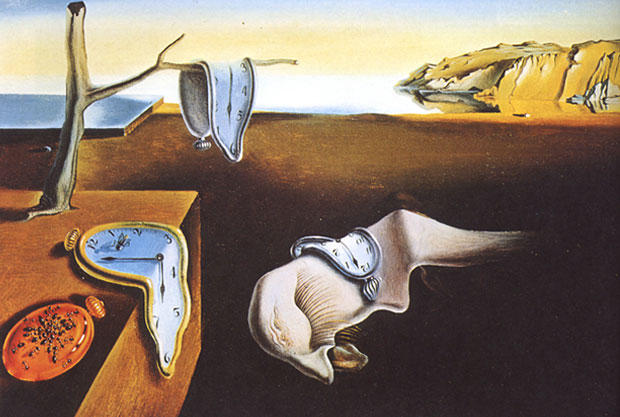

When we look at Dali’s iconic surrealist painting, The Persistence of Memory, we are faced with a kind of threat to all meaning as we know it. Murakami does much of the same, except his method is more in line with another of Dali’s paintings,

. Everything is under the threat of becoming the same, neatly divided into little homogenized boxes. But alongside them, the rest of the undivided world remains—and it is this undivided world that Murakami makes us reconsider the world of desire, fate, grief, memory, and meaning.

Which is why, although I’ve not particularly loved the last two books of his (his epic 3 volume saga 1Q84, and his surrealist masterpiece Kafka on the Shore), I would still recommend him to people.

Brilliant, staggering, awesome, overhyped, annoying, boring—you can call him whatever you wish to. But he is undoubtedly an important author for bringing into scope the entire 21st Century at large and laying bare its motives.

I did not have the heart to finish his newer releases, Men Without Women, or Killing Commendatore, but that is perhaps because I’ve known him so closely – and will perhaps save these books for a day when he feels unfamiliar again.

Srimanta Mitra

Srimanta Mitra is a psychologist, multi-instrumentalist, digital marketer and writer. He has a Master’s degree in Psychology from Ambedkar University, Delhi, and a Bachelor’s degree in English literature from Sri Venkateswara College, Delhi University.